Diego Rivera Murals for the Museum of Modern Art Sugar Cane

Carbohydrate Cane

1931

Fresco on reinforced cement in a galvanized-steel framework, 57 1/8 10 94 one/8" (145.1 ten 239.one cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Herbert Cameron Morris, 1943. © 2011 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, México, D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

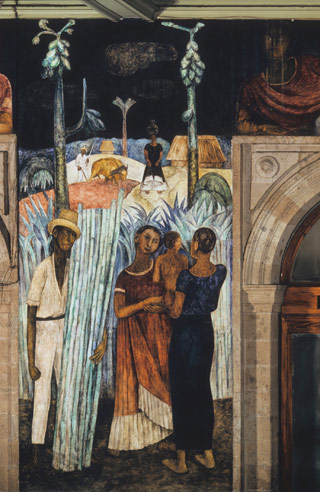

Set on a carbohydrate plantation, this portable landscape introduces the tensions over labor, race, and economical inequity that simmered in Mexico subsequently the Revolution. In the foreground, an Indian woman, with the traditional braids and white clothes of a peasant, cuts papayas from a tree while her children collect the fruit in reed baskets. Backside them, dark-skinned men with bowed heads gather bunches of carbohydrate pikestaff. A foreman, with distinctly lighter peel and pilus, watches over them on horseback, and in the background a pale hacendado (wealthy landowner) languishes in a hammock. In this panel, Rivera adjusted Marxist ideas about class struggle—an agreement of history born in industrialized Europe—to the context of Mexico, a primarily agrestal land until after Earth War Ii.

Carbohydrate Cane is based loosely on a panel from Rivera's mural bicycle at the Palacio de Cortés in Cuernavaca, Mexico. The nigh noticeable change made to this source image is the family unit group added to the foreground of the portable landscape. This detail offers a foil to the harsh scene of exploitation that unfolds in the middle and background of the work. Nonetheless, commentators in the U.S. press immediately recognized the panel's political message, highlighting the "unremitting toil" depicted.

Diego Rivera. Carbohydrate Plantation. 1930. Fresco, approx. 14' three 1/iv" x 111" (4.35 x 2.82 m). Palacio de Cortés, Museo Regional Cuauhnáhuac, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Cuernavaca, United mexican states. © 2011 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, México, D.F./Artists Rights Social club (ARS), New York. Photograph © 2011 Eumelia Hernández, Ricardo Alvarado; Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes

Precedents for Saccharide Cane'due south focus on Indian peasants and workers are found in Rivera's early mural panels at the Secretaría de Educación Pública, begun in 1923. At that time, viewers were unaccustomed to seeing United mexican states's native people as a worthy field of study of loftier art, and many objected loudly to Rivera's large-scale depictions of ethnic figures.

Diego Rivera. Cane Harvest. 1923. Fresco, approx. thirteen' 11 1/4" ten 83 seven/8" (4.25 10 2.13 thousand). North wall of the Patio del Trabajo (Courtyard of Labor), start floor, Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico Urban center. © 2011 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, México, D.F./Artists Rights Social club (ARS), New York. Photo by Schalkwijk/Art Resource, New York

Considered separately from the rest of the panel, the woman and children in Sugar Cane might seem to invoke a picturesque vision of rural life. They recall other works by Rivera that promote a benign, folksy image of Mexico. Oil-on-canvas paintings similar Bloom Day, which won the purchase prize at the Outset Pan-American Exhibition of Oil Paintings at the Los Angeles Museum of History, Scientific discipline, and Art (now known every bit the Los Angeles Canton Museum of Art), appealed to U.South. collectors but irked critics on the left who questioned Rivera'due south political commitment. In Carbohydrate Pikestaff, the indigenous family, paired with a stark portrayal of unjust labor practices, illustrates that Mexico'due south agrarian system exploited non just Indian men but also women and children.

Diego Rivera. Flower Day. 1925. Oil on canvas, 58 x 47 1/2" (147.32 x 120.65 cm). Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles. The Los Angeles County Fund (25.vii.1). © 2011 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, México, D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital image © 2011 Museum Associates/LACMA/Fine art Resources, New York

In Sugar Cane, Rivera frames his limerick equally though he is looking through the viewfinder of a camera. The bodies of the female laborers at the lower edge of the work, for instance, are cut off at the waist, giving the impression that this panel presents just a fragment of a larger composition. Rivera's do of "cropping" his images may stem from his contact with photographers and filmmakers. He was a longtime friend of Tina Modotti, and he worked with the Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein on his unfinished masterwork іQue viva México!

Sergei Eisenstein (Russian, 1898–1948). Film still from іQue viva México! 1931. 35mm prints from unedited moving picture footage. The Museum of Modernistic Fine art, New York. Photograph by The Museum of Mod Art, Department of Imaging Services (Robert Kastler)

Source: https://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2011/rivera/mobile/mural_details/sugar_cane.html

0 Response to "Diego Rivera Murals for the Museum of Modern Art Sugar Cane"

Post a Comment